Burgundy, the Nazis, and Why Pouilly-Fuissé Doesn’t Have Premier Crus

Wine aficionados say that Burgundy is one of the most complex and difficult regions to understand in the wine world. I won’t contest that.Notes from my latest conversation with a passionate producer lie in a pile beside my keyboard, under a map of Burgundy wine country.

Wine aficionados say that Burgundy is one of the most complex and difficult regions to understand in the wine world. I won’t contest that.Notes from my latest conversation with a passionate producer lie in a pile beside my keyboard, under a map of Burgundy wine country.

Eying the latter, I follow the villages south from Dijon, envisioning my former daily commute to Beaune. Marsannay is where the vineyards start. Then there’s Fixin, Gevrey-Chambertin, Vougeot, and Vosne Romanée. Nuits-Saint-Georges, Pernand-Vergelesses, Aloxe-Corton and Beaune. To this point I can almost mark where one appellation ends and another begins. After this point, however, it starts to get hazy. South of Beaune are the villages of Volnay, Meursault, and Puligny-Montrachet. Santenay. Bouzeron. Rully. I tend to lump Chalon-sur-Saone and everything south of it, all the way to Beaujolais, together.

Eying the latter, I follow the villages south from Dijon, envisioning my former daily commute to Beaune. Marsannay is where the vineyards start. Then there’s Fixin, Gevrey-Chambertin, Vougeot, and Vosne Romanée. Nuits-Saint-Georges, Pernand-Vergelesses, Aloxe-Corton and Beaune. To this point I can almost mark where one appellation ends and another begins. After this point, however, it starts to get hazy. South of Beaune are the villages of Volnay, Meursault, and Puligny-Montrachet. Santenay. Bouzeron. Rully. I tend to lump Chalon-sur-Saone and everything south of it, all the way to Beaujolais, together.

I’m not the only one to occasionally overlook southern Burgundy. Most people can name or recognize at least a few Premier Crus or Grand Crus from the Côte d’Or (Charmes-Chambertin, La Tache, Romanée-Conti, etc), but who is that familiar with the various climates (areas, sometimes tiny, known for their distinct terroir) of the Maconnais region? Which premier crus can you name from Pouilly-Fuissé?

That was a trick question. The most distinguished white from the Maconnais, Pouilly-Fuissé – known for its refreshing peach and melon aromas – has never boasted the distinction of Premier Cru, let alone Grand Cru. Yet the region is known for its Chardonnay, which thrives in the warmer climate and limestone soils.

“Je vous explique,” says Jean-Michel Drouin, producer at Domaine des Gerbeaux in Solutré, a small commune attached to Pouilly-Fuissé. He launches into his sans Cru explanation, pausing only occasionally to catch his breath. Over the phone, I hear pots and pans clapping in the background: it’s lunchtime in France.

“In 1940, France was occupied by Germany,” Monsieur Drouin begins, as if delving into the first chapter of a long history. I hear water glasses set on a table. My storyteller decides on the abridged version and continues.

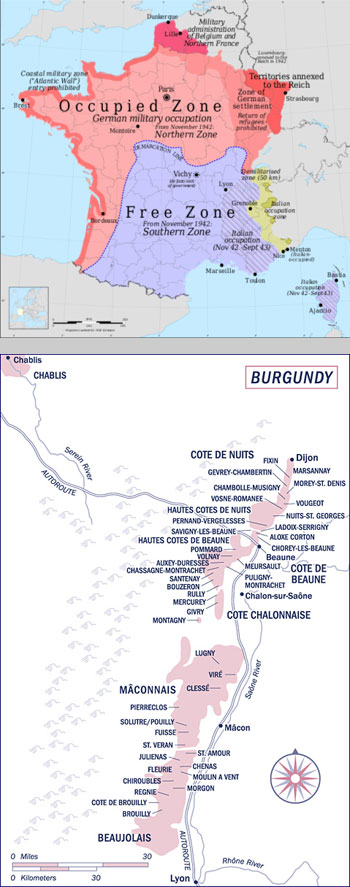

“There was a Line of Demarcation that cut France in two. Northern Burgundy was under German occupation and southern Burgundy – nôtre region – was free. The occupied zone ended at Chalon. The Germans were given permission [by their military authorities] to requisition any wine except the ‘first growths.’”

(At that time the Premier Cru appellation category had not yet been established.)

To save the wines and protect French tradition, “all the winemakers of the Côte d’Or got together and in one week designated as many of the best vineyards as possible [those that had not already been given the Grand Cru distinction] ‘Premier Cru.’ In the Maconnais, we don’t have the same appellation, but we have a system of climats such as Les Champs Roux, La Mure, Les Gerbeaux; these are vineyards that have been indexed by our ancestors as producers of grandes cuvées…”

Later, I search a map of France that shows the World War II line of demarcation. I superimpose the image onto a map of Burgundy wine country. Sure enough, the line juts up from Bayonne in southern France toward Tours, then serpentines east, making a lucky horseshoe that seems to exclude the lower tip of Burgundy vineyards by sheer accident.

Was the Premier Cru distinction developed, then, on political grounds? Monsieur Drouin hints that at least its roots reside in a brilliant and lesser known French resistance against the Germans.

The question that begs to be asked is this: if the Germans marched in and took over Paris, what would keep them from commandeering any wine, especially those wines deemed higher quality?

It turns out there is a lot more to the story, but Monsieur Drouin’s abridged version leads me to the crux of the matter. In an article entitled Négoce des vins et propriété viticole en Bourgogne durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale,(“The Wine Trade and Viticultural Property in Burgundy During the Second World War”), Christophe Lucand explains in detail that the Nazis did establish and follow laws that required them to work de gré à gré – by mutual agreement – with Burgundy negociants, if for no other reason than to ensure efficiency in delivering large quantities of wine to their troops, as well as in exporting it to Germany.

The laws identified lower quality wines to be requisitioned for troops; the better wines were purchased for exportation to Germany. By establishing an intermediate appellation between village level wine and the Grand Crus, Burgundy winemakers spared a large quantity of wine from appropriation.

Which brings me back, after all, to Monsieur Drouin’s point: because Pouilly-Fuissé found itself happily south of the Line of Demarcation, it had no pressing need to inaugurate Premier Cru vineyards at the time. (They are, he adds, currently in the process of applying with the INAO to obtain the Premier Cru appellation.)

So, what of this Cru-less region below enemy lines? Naturally, Monsieur Drouin defends it as just as worthy as its northern counterpart, although he says it is more “complicated” than the Côte d’Or.

“In the Côte d’Or it is easier,” he says conclusively. “You have the flatland vineyards and the mid-slope vineyards and the haute côte vineyards, with their own merits. But where we live, the geography does not help to distinguish. You have valleys that are better than mid-slope vineyards, and mid-slope vineyards that are better than valleys. There are a multitude of different soils that make Pouilly-Fuissé wide-ranging. The Maconnais is vast and complex.”

He gives a little cluck. “How to distinguish the real Pouilly Fuissé? I’m always asking myself this question.”

Jean Michel Drouin’s Domaine des Gerbeaux comprises 13 hectares (32 acres) in the Maconnais region, 98 kilometers south of Beaune. He and his wife Béatrice, their son Xavier and their daughter Laetitia all work at the domaine to maintain the family business. Sixty small parcels (the largest of which is just shy of 2 acres in size) span the 13 hectares, and the wine from each parcel is produced separately. Monsieur Drouin calls this “microvinification.”

“It’s a bit of an “épicérie,” he says, referring to the variety of wines he produces and sells. “I make seven different Pouilly-Fuissés, three Macons, two Saint -Vérans, and one Pouilly-Vinzelles.

“Someone who tastes a very good Pouilly-Fuissé from Chaintré and then tries a Pouilly from Vergisson might not know it, but it’s not the same wine. Regarding taste, aroma, and structure of the earth, there are five completely different terroirs amongst the five communes.”

Will the eventual addition of “Premier Cru” augment the quality of the wines from the Maconnais?

“If one day we have Premier Cru vineyards, they will be those that have already been distinguished by our ancestors years ago as the vines that give superior Pouilly-Fuissé,” says Monsieur Drouin.

“We have exceptional vineyards that produce exceptional wines.”

Point taken. I’ll be keeping my eyes on the wines of southern Burgundy for a change.

Image Credits: Eric Gaba & Rama, Wikimedia; wineaccess.com

Emily L. Turner is an American writer and budding photographer who divides her time between her old Kentucky home and Burgundy, France. She began her life in France as an exchange student in Dijon, then taught English to primary students for a year in Beaune, and is now pursuing her passion for wine. In addition to freelancing for several print magazines, she writes about her experiences on her blog, EmilyintheGlass and loves to hear from her readers!

by Emily L. Turner

Emily's blog: http://emilyintheglass.wordpress.com/

Luxury hotels and designer Bed and Breakfasts in Burgundy Business hotels and Secret places